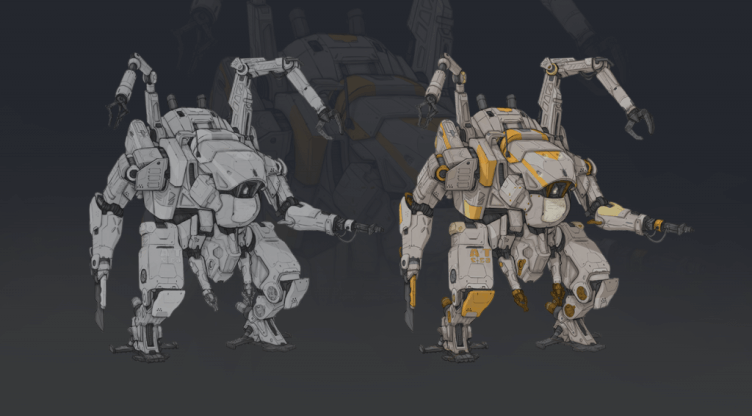

When you start building a game, 3D modelling software quickly becomes part of everyday work. Characters, props, environments – all of them pass through the same tools again and again. The choice you make early on affects how fast assets come together and how painful changes feel later in production.

Most developers don’t stick to one perfect tool. Some begin with simple, free software to learn or prototype ideas. Others move to paid solutions when asset complexity increases or deadlines get tighter. In real projects, tools are often chosen based on habit, team size, and what needs to be built right now – not on feature lists.

This text will help you make sense of all the 3D modelling software most commonly used in game development today. The goal is to show where each tool actually fits, based on real workflows and production needs.

How to Choose 3D Modelling Software for Game Development

Most people don’t choose a 3D modelling tool by comparing features. They choose it based on what they end up opening every day. If you spend hours tweaking characters, you start caring about anatomy tools and rigging. If you build environments, modular pieces and clean exports matter more. When you work alone, speed usually wins over depth.

Over time, the software either stays out of your way or becomes something you fight with. That’s usually when developers realize that the “best” tool on paper isn’t always the best one to work with.

It’s also worth paying attention to how the software behaves once assets leave it. Export settings, scale, and materials can either flow straight into the game engine or turn into constant cleanup. Over time, those small frictions add up more than most people expect. A tool that looks powerful on its own can slow things down if assets need constant fixes after import.

Learning curve also plays a bigger role than many expect. Some tools are easy to pick up but limited later. Others feel complex at first but grow with the project. Teams often choose software they already know, simply because it keeps production moving without friction.

Last but not least comes the budget and licensing. It’s especially important for smaller teams. There’s a lot you can do with free tools, but of course, paid tools bring lots of new opportunities. When the project is getting serious, the investment in quality software can give the production team a good boost.

The key point is that free versus paid isn’t a skill gap. It’s a workflow decision. Knowing when a tool helps you move faster – and when it gets in the way – matters more than whether it costs anything.

Best Free 3D Modelling Software for Games

Free tools are often where real work begins. Not as a compromise, but as a practical choice. They’re easy to access, quick to set up, and good enough to get assets into a game without overthinking the pipeline. For many developers, these tools stay in use far longer than expected.

What matters here isn’t whether a tool is free, but whether it can handle game-ready assets. Clean topology, proper UVs, reliable exports, and decent performance inside the engine make a bigger difference than advanced features most projects never touch.

Most free 3D design programs don’t try to be everything at once. They have the most basic functions like shaping meshes, unwrapping UVs, and exporting assets. For game development, that’s often enough. What matters is whether the tool helps you finish a 3D project without adding extra steps.

Many developers use these tools as their main software for 3D game assets, not just as a learning stage. They handle props, environments, and even characters, as long as the scope stays realistic. In practice, good game 3D modeling tools are the ones that stay predictable when assets move from the editor into the engine.

Free tools also make it easier to experiment. You can try things out, block levels, or rebuild assets without thinking about licenses or subscriptions. That kind of freedom matters more than it sounds. It’s one of the reasons studios keep using free tools early on, or quietly rely on them for internal prototyping.

What follows aren’t just popular names pulled from lists. These are the free options that show up again and again in real workflows, especially when the goal is to move forward and get something playable on screen.

Blender

Blender is usually the first name that comes up, and for good reason. It’s one of the few free tools that can carry a project far beyond the prototype stage. For me, as a head of 3D department, it’s my personal favorite.

For game work, Blender covers most of what you actually need. Modeling, UVs, basic sculpting, and export all sit in the same place. Most days, Blender doesn’t ask for much attention. You make an asset, drop it into the engine, and move on. After a while, you stop noticing the software at all. For a lot of teams, that’s the point — if the tool stays quiet, the work goes faster.

The start can be rough. Menus everywhere, shortcuts that don’t make sense yet, things hidden where you don’t expect them. Once the basics settle in, though, it covers most everyday tasks without pushing you to juggle several tools at once. For many 3D projects, Blender isn’t a “free alternative” — it’s just the tool that gets the job done. For advanced users, there are many add-ons for Blender, both free and paid, that help simplify and fasten the work.

Substance painter

Substance Painter usually comes in after modeling is done. It’s focused on texturing, and that’s where it earns its place. Instead of painting flat images and hoping they fit, you work directly on the model and see the result in real time.

For game assets, that makes a difference. Materials react properly, details feel more grounded, and what you see in the viewport is close to what ends up in the engine. It’s especially useful when working with PBR workflows and keeping consistency across multiple assets.

At Kevuru, we use it for both characters and environment. Most teams pair it with other 3D modeling tools for games rather than using it on its own. But when it comes to final surface quality and believable materials, Substance Painter is often the step that brings an asset to life.

SketchUp

SketchUp Free feels closer to drawing than traditional 3D modeling. You push and pull shapes, stretch forms, and block things out quickly. For simple environments or layout ideas, that speed can be useful, especially early on.

It isn’t designed with game engines in mind, so exports usually need some cleanup. That said, for rough level layouts, architecture-style scenes, or quick spatial tests, it works without much setup.

Most developers don’t keep SketchUp in the pipeline for long, but it can help answer early questions. When you need to test scale, spacing, or overall structure before committing to detailed assets, it gives fast answers without slowing things down.

Moving From Free to Paid Tools

At some point, free 3D modeling tools for games start to show their limits. Not always in obvious ways, but in small things that slow work down. Managing large scenes becomes harder. Collaboration takes more effort. Certain tasks start to feel like workarounds instead of normal steps.

That’s usually when paid software enters the picture. Not because it’s automatically better, but because it removes friction. Features that once felt optional begin to save real time. For teams working on bigger 3D projects, those gains add up quickly.

Paid tools tend to make sense when production is no longer experimental. Deadlines matter more, assets pile up, and consistency becomes critical. The switch isn’t about leaving free software behind — it’s about choosing tools that match where the project is now.

Autodesk Maya

Maya shows up once projects get serious, especially when characters and animation are involved. It’s been around long enough that many studios build their pipelines around it, and a lot of artists already know their way through the interface.

What Maya does well is consistency. Rigs behave the way you expect, animation tools are stable, and assets move through production without surprises. For teams with several artists, that kind of predictability usually matters more than extra features. When tools behave the same for everyone, work moves more smoothly and problems show up less often.

Maya isn’t a lightweight option, and it’s rarely where solo developers begin. But for projects that depend on reliable animation workflows and long production cycles, it’s easy to see why 3D animation team at Kevuru keeps using it: Maya satisfies almost any need they have.

Autodesk 3ds Max

When I started working as a 3D environment artist many years ago, 3ds Max was my primary tool. It suits the needs of environment art creation best. It’s widely used for props, level pieces, and larger scenes where structure and reuse matter more than character work. Many artists rely on it for building clean, modular assets that slot into a game without surprises. Since then, I have changed tools, but still can advocate for 3ds Max as a great software for working with 3D.

The workflow feels direct. You don’t spend much time getting ready before you can start working. You open a scene, adjust what needs changing, and move on. On projects with lots of props or large environments, that speed starts to matter, especially when revisions come in late and there’s no time to rethink the setup.

3ds Max isn’t something most beginners pick up first. But when a game leans heavily on environments, architectural pieces, or repeatable assets, it often ends up being the tool teams rely on to keep production steady rather than fighting the software.

ZBrush

ZBrush lives in its own space. It doesn’t behave like traditional modeling tools, and it doesn’t try to. The focus here is shape and detail, not clean meshes or engine-ready assets.

Artists usually open ZBrush when something needs character. Faces, creatures, worn surfaces, and organic forms are where it shines. You push and pull the model like clay, without worrying about topology at first. That freedom is why it’s hard to replace once you get used to it.

ZBrush rarely works alone. Models usually move out of it and into other software for cleanup, retopology, and export. But when a project needs strong visual identity or high-detail assets, ZBrush is often where that work starts.

Cinema 4D

Cinema 4D has a good reputation among 3D modelers because it feels light to work with. Artists coming from motion design or visual work usually get comfortable fast, simply because the interface doesn’t fight back.

In game projects, it often shows up where style matters more than strict realism. It’s easy to shape forms, adjust scenes, and try variations without slowing down. When the task is to explore ideas or rough out assets before committing to heavier tools, it fits naturally.

Most studios won’t build a full game with Cinema 4D. Still, it shows up when teams want flexibility and speed without fighting complex systems. For certain projects, that ease of use outweighs the lack of deep game-focused features.

Houdini

Houdini works differently from most modeling tools. Instead of pushing vertices around, you build small systems that create the result for you. It can feel awkward at first if you’re used to working by hand, but that shift is also what makes Houdini so useful once it clicks.

It’s most useful when assets need variation or scale. Terrain pieces, destruction, procedural buildings, or anything that would be painful to edit one by one are common use cases. Once a setup works, you can change inputs and get new results without rebuilding everything from scratch.

Houdini isn’t something teams pick up casually. Houdini isn’t a quick learn, and plenty of teams never use it. But when a project grows complex, with big worlds, repeated elements, or constant late changes, it can take a lot of manual work off the table and make those changes far less painful.

Comparison

| Software | Pricing (approx) | Best For | Common Use in Games |

| Blender | Free | All-around 3D design | Characters, props, environments |

| Wings 3D | Free | Fast modeling | Simple props, blocking |

| SketchUp | Free; Paid plans ~$119/yr | Layout & quick ideas | Rough blocking, spatial tests |

| FreeCAD | Free | Precision, technical pieces | Mechanical props, accuracy-based 3D objects |

| Autodesk Maya | ~$235/mo ($1,875/yr) | Animation, characters | Rigging, animation pipelines |

| Autodesk 3ds Max | ~$215–$245/mo ($1,875/yr) | Environments & props | Modular assets, large scenes |

| ZBrush | ~$40/mo or ~$360/yr | High-detail sculpting | Characters, organic forms |

| Cinema 4D | ~$60/mo or ~$720/yr | Stylized assets & motion workflows | Concept work, stylized props |

| Houdini (Indie) | ~$269/yr (Indie); FX higher | Procedural & large systems | Terrain, procedural elements |

Choose the Right Tool for Your Project With This Checklist

By this point, it’s usually clear that there’s no single setup everyone ends up with. Most teams mix tools based on what they’re building and where the project is headed. A free tool might handle early assets just fine, while a paid one steps in later when production pressure increases.

What usually matters most is how the software behaves once it’s part of the pipeline. If assets drop into the engine without surprises, updates don’t cause new issues, and artists aren’t wrestling with the tool day after day, that’s when things tend to work. Features matter, but friction matters more.

The list above is not the full stack we use at Kevuru. Depending on the pipeline, we also add Marvelous Designer (works great for clothes and fabrics), Substance Designer (materials creation), Plasticity, Character Creator, UV Layout, 3d Coat. It’s impossible to master every tool from the very start, but they become useful once the complexity of projects rise and artists advance into more detailed objects.

In practice, the “right” choice is often the one that helps the team keep moving without reworking the same problems. Tools come and go, but workflows tend to stick.

To help you make your mind when starting work, go through this checklist of questions to ask your team before making the decision.

- What type of assets are you building most – characters, environments, props, or a mix

- How complex the project is – a small prototype or a long production cycle

- Whether assets move cleanly into your game engine without constant fixes

- How steep the learning curve is for your team right now

- If collaboration and version control matter for this project

- What your budget allows today, not just what looks ideal on paper

- How easy it is to adapt when the scope or direction changes

Every project ends up needing something different. What works well in one game can get in the way in another. The best tools are the ones that quietly support the work and don’t demand attention. Do you want to learn more about 3D modeling? Read on to find out how our artists create 3D characters for AAA games.